I recently moved to

Madison.

Like any relocation process, the first few weeks involved a lot of figuring stuff out.

My list of priorities included: opening a new bank account, buying groceries, obtaining miscellaneous household items, mailing letters and packages to friends, putting some cold beer in the fridge and some decent tequila on the shelf, finding my way to work and around campus, testing out several Mexican restaurants to find my “regular” one, etc.

Well … first things last.

I need an Internet connection!

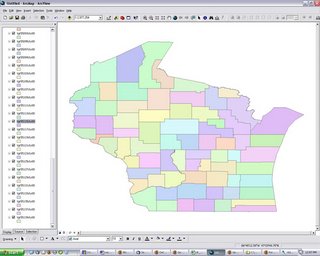

Once that was up and running it was smooth sailing. Simple searches like “music stores in Madison” or “sushi near Emerald St.” in Google maps gave me several options, the knowledge to find my way there, and any relevant contact information. In other words, I had an immediate plan of action. All I needed to do was print out a map (or scribble down my own simple version of one) and jump on my bike, armed with the knowledge to navigate my way through an otherwise unfamiliar urban landscape.

Throughout this process I marveled at the usefulness and efficiency of this resource. In the past I was forced to rely on phone books, crude city maps, and confusing directions from locals too familiar with the place to grasp an outsider’s limited perspective. Within just a few days I found such staples of daily existence as a coffee shop, liquor store, and wig emporium (no fly shops in Madison!?). But this appreciation was coupled with another unsettling thought: what if I didn’t have this resource? I’d be completely lost! (insert dramatic music here.)

The philosophical implications of this speak to how the use of Google maps informs the development of my geospatial understanding of Madison. I construct a conceptual landscape within my mind before actually experiencing Monroe Street or John Nolen Dr. When actually riding through the streets there is a process of fitting what I experience with what I expect to find … a representational negotiation of sorts. “Oh, here’s where University Ave splits into Campus Dr and University Ave. Here’s that causeway stretching across the corner of Lake Monona.” Sometimes it seems the map is wrong. “Hmm … Exotic George is actually on the corner of Dominion Dr, not Rustic Dr.” But such glaring examples efface a more subtle process by which my virtual understanding of the landscape actually constructs (or constrains?) my experiential understanding of it. The following example attempts to illustrate this point.

I can’t find a local hardware store, so I guess I need to actually drive to Home Depot. Ugh. Oh well, “there it is by the intersection of the W. Beltline Hwy and Verona Rd.” So I’m driving and I make the left onto Verona… I’m looking to my right, “the Home Depot is here somewhere…”. I’m exiting to the right. “Oh there it is.” I pull up to it and park. I’m in front of the Home Depot because I am at the place where the map said it’s located. I get out of the car and… “Wait! This isn’t Home Depot. This is some other store. But it can’t be. This must be Home Depot… but it’s not. This is an auto parts store. Something must be wrong with this place. Maybe this neighborhood hasn’t updated itself to fit with the Google map yet?” Turns out Home Depot was there, just behind that store and across a parking lot. But reality was not conforming to my Google-informed mental map. Somehow the virtual representation had superceded the experiential representation of the place. Google >= reality.